Johnnie Simmons: Gullah storytelling in images and words

STORY BY CAROLYN MALES

STORY BY CAROLYN MALES

Special to Local Life Magazibe

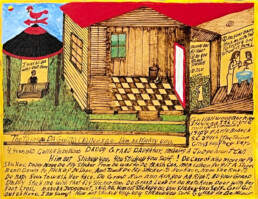

It all began with a rock. The kind of ordinary rock you and Imight walk right past without seeing. But for Johnnie Simmons, this cantaloupe-sized chunk of stone became a symbol of renewal, emblematic of what would be a sea change in his life. It would eventually lead him to a career in art as a storyteller, documenting everyday life in his wood-burned pictures captioned in a mix of Gullah and English.

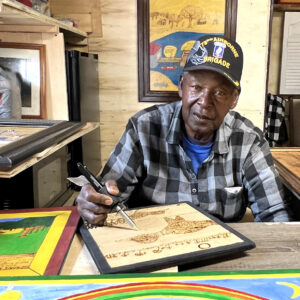

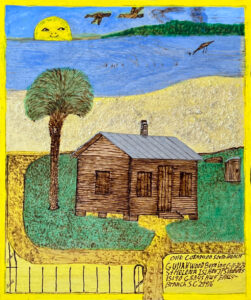

At the time, troubled by nightmares and flashbacks dating back to his service as a paratrooper with the 173rd Airborne in Vietnam in 1970, Simmons had sought help for post-traumatic stress disorder. Thirty-two years later, he’d found understanding and hope along with coping skills in a six-week program at a trauma treatment center in Salem, Virginia. On a break, he’d walked out into an adjacent field and come across the rock. “It looked as if a lawn mower had hit and chipped it and then hit it again and chipped out another piece,” Simons remembers. “Bam! The shape of the rock looked just like a lion’s head, so I picked it up and cleaned it off.” He headed back into his program and there during an arts and crafts session he grabbed a marker and painted in a mouth, nose, eyes and hair. “Lion Rock” would become his symbol, his mascot, his talisman and would appear in his artworks – as a face in the sun, a sign on a building, a knot in a tree…

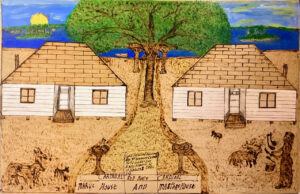

Today Simmons’s work is on display at Four Corners Gallery, Penn Center, and Willie’s restaurant on St. Helena. He works out of a one-room building fronting his house, a vegetable garden and pens of goats and chickens. Walking around looking at his works on shelves lining his studio walls is like reading a storybook of tales from his life on St. Helena – immersive baptisms, school buses, praise houses, farm life, fishing and, yes, ghosts and angels.

Today Simmons’s work is on display at Four Corners Gallery, Penn Center, and Willie’s restaurant on St. Helena. He works out of a one-room building fronting his house, a vegetable garden and pens of goats and chickens. Walking around looking at his works on shelves lining his studio walls is like reading a storybook of tales from his life on St. Helena – immersive baptisms, school buses, praise houses, farm life, fishing and, yes, ghosts and angels.

[Local Life] Much of your artwork tells stories from your past.

[Johnnie Simmons] I grew up on Pine Grove Plantation in Frogmore on St. Helena with my parents, grandparents, three brothers and two sisters. We were farm people. We grew corn, tomatoes, cucumbers, okra, rice and beans and raised cows, chickens and hogs. We worked hard and went to church. My grandpapa was a minister at St. James Baptist Church

[LL] I see you’re wearing a 173rd Airborne Brigade cap from your time in Vietnam.

[LL] I see you’re wearing a 173rd Airborne Brigade cap from your time in Vietnam.

[JS] I was drafted after high school graduation. I was sent to Fort Gordon and then to Fort Benning where I went to jump school for three weeks and became a paratrooper. From there they gave me orders to Vietnam and the Landing Zone Uplift army base. I went there and did what I had to do. After 11 months and 11 days, they shipped me home for Christmas. Being home was a whole new experience. The weather was different. My mind set was different… everything was different. I thought everything was all right, and then a firecracker went off. I went running down the middle of the street. Everyone was looking at me, but oh, God, I was still alive. I finished my tour at Fort Hood, Texas, with the 75th Rangers. Then I came home and went to tech school on the GI Bill. I ended up at a company working with heavy equipment—bulldozers, front-end loaders and stuff like that. I later did that on Parris Island. During all that time I was in the National Guard and retired with 15 years and 11 days combined time.

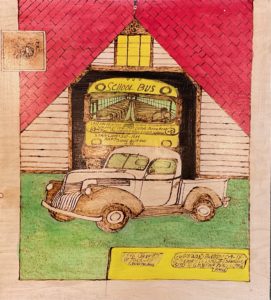

[LL] School buses appear in a lot of your artwork.

[LL] School buses appear in a lot of your artwork.

[JS] In 1989 I resigned from my Parris Island job and drove school buses for 10 years. When commercial licenses for drivers became the law, I was asked to teach people driving skills to help them pass the test. That’s how I met my wife, Cynthia. She taught the classes, and I taught the hands-on driving. We were a team and did real good.

[LL] How did you get from painting the lion rock to woodburning art?

[JS] I had started doing more rocks, and when I went to the Vietnam Memorial Wall in Washington, I left one there. Then one day I had a tire leak and went to get it fixed at Walmart. They were slow getting it repaired, so I walked into the store and wandered around. In the arts section I saw where they had a wood-burning tool set. I thought that might be something I could do. I bought it and started playing around with it and, lo and behold, the art began to flow. I began drawing things from before the military – the farm, fishing, and other scenes from when I grew up. I would write down the things that I heard from my parents, grandparents and different people. Sometimes I’d hear religious things and put a story to it.

[LL] Along with your more secular pieces, your work embraces your deep faith. I’m looking at a portrait of you and your father. You’ve got tears running down your face, and your father is saying that sometimes it rains in your life. But God is still in control of your life. Trust him.

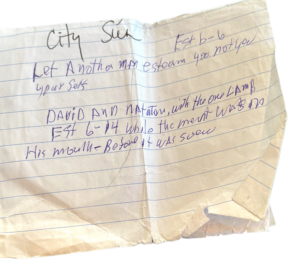

[JS] I was pastor at Scottsville Baptist Church for five years, and now I preach third Sundays teaching children and Monday nights online. I write down stories for sermons and art on scraps of paper. [In illustration he takes out his wallet and pulls out a small piece of notebook paper where he’s written, “Let another man esteem you, not you, yourself.” ] I do things that help me. When I put it on paper, it helps someone else. I work at night when it’s quiet. And when I get into a piece of art, I can stay on it for two or three hours, sometimes through the night.

[LL] I’m told just as you “read” your lion rock, you “read the wood” before you pick up your burning pen tool.

[JS] I come up with the idea and then study the grain of the wood and see if there’s anything in it. Like there might be a pattern that could be water and another, sky. I draw with pencil, turning the wood to make the grain do what I want to do. Then I burn the drawing into the wood and paint it – but sometimes I leave it natural — and seal it.

[LL] There’s also lots of humor in your work — a dogs’ poker game, with one pooch running away when he’s lost too much money and the others yelling at him “All Dues Must Be Paid Up.” And there’s the painting where your wife’s hair has a mishap with a sticky fly strip that you’ve placed over a trash can. The dialogue between her and your granddaughter debates who’s at fault.

[JS] I do a lot of humor if I can. The art is a means of expressing myself and getting rid of some of that Vietnam thing. It takes me back to when the times were good. I create some of it, and some of it I live.